A man who reportedly communicated through drawing before learning the ability to speak and whose first word was pencil, the Spanish “piz,” certainly seemed fated to become one of the most recognized artists of his century.

Although these particular details may be a bit of exaggerated myth-making (they come from his mother’s accounts of his childhood), few similar greats have the same colorful backstories as this artist. Pablo Picasso — or as he was born, Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso — died on this day, April 8. In memory:

Here are five stories to color your understanding of the late Cubist founder.

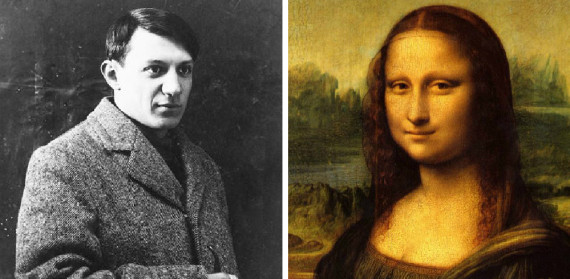

1. It is now believed that Pablo Picasso had a hand in stealing art from the Louvre before he was famous. He was also accused of stealing the “Mona Lisa.”

In 1911, authorities discovered that Picasso was in possession of two Iberian statues that were stolen from the Louvre by his known acquaintance, Géry Pieret, four years earlier. (A good friend of Picasso’s at the time, Guillaume Apollinaire, employed Pieret as a secretary.) At the time, the artist claimed he had no idea that the statues were stolen, but in recent years it has been argued by art historians such as Silvia Loreti and art history professor Noah Charney, that Picasso had full knowledge of the origins and may have even commissioned the heist. The entire ordeal has gone down in history as the “affaire des statuettes.”

In Charney’s paper, “Pablo Picasso, art thief,” the professor concludes that there is “beyond reasonable doubt” that Picasso requested the theft, partly because the statues aligned specifically with his tastes and he actively hid the works while openly displaying other similar possessions. Charney further explained:

Picasso was a regular visitor to the Louvre and a passionate admirer of Iberian art, which he felt was the root of all Spanish art. It is inconceivable that he would not recognize the statue heads presented him by Géry Pieret … It is also beyond plausibility that Géry Pieret would randomly choose to steal a pair of statues that were so ideally suited to Picasso’s tastes, and then happen to offer them … to the Spaniard.

As the New York Times described, Apollinaire and Picasso were both in a sort of clique around this time. What led to the discovery of Picasso’s stolen art was that these two were accused of the bigger crime of stealing the “Mona Lisa.” Both were questioned during investigations, and Apollinaire — who had signed an agreement to “burn down the Louvre” — accused Picasso of the crime. They were both eventually let go and two years later it was discovered that a former Louvre employee, Vincenzo Peruggia, had hidden Leonardo da Vinci’s masterwork in his small apartment.

Images: Pablo Picasso / Commons.

2. When he was only nine years old, Picasso completed his first painting — “Le Picador.”

Picasso’s father was a painter himself and taught his son at a young age, leading Picasso to finish “Le Picador” before he was even in the double digits.

A few years after this, Picasso enrolled into the School of Fine Arts in Barcelona, where his father was employed, and ended up renting him a studio. Around this time, Picasso finished his “first large academic canvas” in 1895, which was called, “First Communion.”

Apparently, his father vowed to give up his own painting when Picasso was just 13, as the young child had already surpassed him in talent.

Images: Pablo Picasso / Commons.

3. Picasso would carry around a revolver loaded with blanks and fire at people he found dull.

As historian Arthur I. Miller (not the playwright) details in his book, Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time And The Beauty That Causes Havoc, Picasso was inspired by the lifestyle and works of French writer Alfred Jarry. One of many quirks associated with Jarry was his habit of carrying around a loaded revolver.

For a time, Picasso seemed to be mimicking Jarry, carrying around a Browning revolver of his own, filled with blanks. Miller explains:

He would fire at admirers inquiring about the meaning of his paintings, his theory of aesthetics, or anyone daring to insult Cézanne’s memory. Like Jarry, Picasso used his Browning as a pataphysical weapon, in a sense playing Père Ubu au natural, disposing of bourgeois boors, morons and philistines.

For the uninitiated, “Père Ubu” was a character in an early play of Jarry’s. In the work, Ubu has a conversation with his conscience about how harder sciences like geometry needed to be inserted into conversations of art, mainly because Friedrich Nietzsche had recently declared God dead and artists, Jarry implied, needed to fill the epistemological void.

Image: Getty

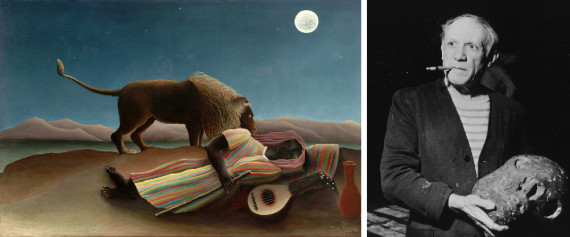

4. Henri Rousseau was “discovered” by Picasso, who found Rousseau’s art so terrible, it was good. Picasso held a party to mock Rousseau’s art, but instead accidentally catapulted him to fame.

The artist Henri Rousseau — also known as Le Douanier (customs officer) Rousseau, as his day job was as a toll collector — was barely recognized as an artist during most of his life, and, for the most part, only received fleeting recognition from the Parisian avante-garde. Writer Paweł Soszyński details this in length along with a particular joke party and faux-celebration of Rousseau’s work that Picasso held early in his own rise to fame, which largely changed the way history remembers the artist behind “The Sleeping Gypsy.”

Soszyński describes how Picasso claimed that he’d found Rousseau’s artwork in a junk shop as a teenager. This encounter ended up sparking an ironic love of the little known — and much older — artist. Eventually Picasso started inviting Rousseau to hang out with his friends, which Rousseau apparently didn’t understand was anything but earnest. Rousseau was self-assured in his genius and just wanted an audience.

In 1908, the then wealthy Picasso decided to throw a lavish party in his apartment, bringing in flags and other such accoutrements to capture the vibe of a grand ceremony, like a French Independence Day celebration. Rousseau was invited along with other up-and-coming artists of the day, most of whom were in on the joke, like Gertrude Stein. People drank excessively, more established art critics crashed, and the party became part of art legend.

Thinking that this truly had been an honor, the extremely drunk Rousseau allegedly pulled Picasso aside at the end of the night and said, “You and I are the greatest painters of our time.” Rousseau continued, “You in the Egyptian style, I in the modern!”

Image Left: Commons. Image Right: Getty.

5. A Nazi officer raided Picasso’s Parisian apartment, and after seeing a photograph of “Guernica,” asked the artist if he had done it. Picasso responded “No, you did.”

This may be a bit of a tall tale, but as the story goes, Picasso stayed in Paris throughout the Nazi occupation of WWII. During that time, the Gestapo decided to raid his apartment, possibly due to his rumored ties in helping with the Resistance. A Nazi officer viewed a picture of “Guernica” on Picasso’s wall and asked, with disgust, “Did you do that?” Picasso’s reply was simply, “No, you did.”

Another similar story recalls the Nazis offering coal to Picasso to to heat his apartment. Picasso’s response: “A Spaniard is never cold.”

Image: Getty

In death, Picasso was remembered as “the titan of 20th century art.”

The New York Times obituary began by calling the late artist “the titan of 20th- century art.” In his last few years, his work was apparently “less tortured,” involving “much more softness,” according to a festival curator who was planning on exhibiting over 200 of the artist’s last works. Picasso was 91. Four of Picasso’s works (“Le Rêve,” “Garçon à la pipe,” “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust” and “Dora Maar au Chat”) still remain in the top 15 most expensive paintings ever sold.

R.I.P., Pablo.

– This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.