Photos by Heather Marie Photography

Nash Grier has a tendency to wreak havoc on malls. One time in Iceland, a single tweet about his whereabouts brought 5,000 girls to a shopping center in search of Nash and his sidekick, Jerome Jarre.

“The mayor of Reykjavik said they’d never seen that, even when The Beatles came 30 years ago,” Jarre said later.

Then there was the incident in St. Louis. One minute, 16-year-old Nash, his 14-year-old brother, Hayes, and his 19-year-old best friend, Cameron “Cam” Dallas, were jostling each other through a sleepy mall that looked one “for lease” sign away from closing. The next moment, flocks of teenage girls, summoned by some unspoken signal, descended in a swarm of outstretched arms to gawk at three Internet celebrities they’d only ever seen on cell phone screens.

“You’re so hooooottttt,” someone wailed.

Girls brought their phones to their faces and stared at Nash through blinking iPhone cameras, as if gazing directly at his highlighter-blue eyes might be as dangerous as gaping at the sun. The shop clerks, all older, seemed at a loss.

If you think One Direction might be a rehab clinic, chances are you’ve never heard of Nash. Among smartphone-carrying girls from 12 to 20, however, he’s already being compared to Bieber.

A little over a year ago, Nash, a rising junior from the suburbs of Charlotte, North Carolina, used his iPhone to do what millions of American teenagers have done: He joined Vine, a social media site launched by Twitter to share looping videos that are up to six seconds long. He started posting bite-sized clips filmed in his bedroom, or, for something truly exotic, the local Wal-Mart. These mini-movies, with titles like “When you can’t find your phone in your pockets…” trade on the mundane minutiae of high school life, and they drive girls wild. In that particular clip, Nash rummages through his pockets for his phone, finds nothing and hurls the pillows off a sofa. “You are awesome  my inspiration every day

my inspiration every day  ,” gushed one of the hundreds of thousands of comments posted to videos like that one.

,” gushed one of the hundreds of thousands of comments posted to videos like that one.

Nash’s Vines have rough edges that make them look as though they’ve been shot by a bunch of high schoolers messing around. Because frequently, they are. There’s Nash shimmying on a snowboard, and Nash riding a shopping cart. His most popular Vine, which has 1.3 million “likes,” is a selfie filmed in his parents’ SUV. He records himself looking quizzically at his kid sister as she mangles the lyrics to Lorde’s pop hit “Royals” — “You can call me queen bee” transforms into “You can call me green beans.”

Like chugging a Red Bull laced with Pixy Stix, the videos hit female adolescents with the emotional equivalent of a sugar high. They’re carefully-edited, six-second jolts of humor that are big on action, short on subtlety and long on relatability. Jarre, who co-founded a Vine marketing company that previously worked with Nash, calls it “snack content.” And it’s true: The videos may not be particularly good for you, but to his target audience, Nash’s Vines are as addictive as junk food.

His 9 million followers have earned him the top spot on Vine, ahead of bigger names like Jimmy Fallon, Ellen Degeneres and yes, even Bieber. (Vine, which has over 40 million members, declined to share the age breakdown of its audience, but marketers who work closely with the service say it skews young, toward people Nash’s age.) Add Nash’s Vine following to the number of fans watching him on Instagram (6.2 million), YouTube (3.3 million) and Twitter (3 million) and you’ve got a kid with higher social media ratings than the White House. Startups, salivating after Nash’s devoted audience, have offered the teen shares of their companies in exchange for a retweet, according to his managers. Nash’s team also confirmed that major brands will pay the star between $25,000 to $100,000 to plug their products in a six-second clip and share it with his fans.

Nash has reached those heights in spite of several major controversies that have already plagued his short career. He’s been called sexist, racist and homophobic in connection with a Vine telling girls how to be attractive; another video mocking Asian names; and a clip in which Nash suggests only gay people are afflicted by HIV, then shouts “fags!” while barely hiding a grin. Nash apologized for the HIV clip, claiming he’d been “in a bad place” when he posted the video, since deleted, in April of last year. Yet that “bad place” seems to have been more than a few-month phase: He’s also purged multiple pejorative tweets about “homos” or being a “damn queer” that once littered his Twitter feed, as well as a post from May 2012 that read, “Gay rights? Nahhh.”

Those uploads, whether they reflect Nash’s beliefs or are merely the thoughtless mumblings of an immature teen, run counter to the “clear-eyes-full-hearts” image Nash tries to foster. The goal of his Vines “is really to make people smile,” he said. And for a certain class of adolescent, if you tried to design the world’s most viral human, you couldn’t do better than Nash.

He’s got prom king good looks and magnetic, made-for-selfie blue eyes. He’s hilarious, at least according to the teens watching him, who happen to be among the most wired people on the planet. He’s a relentless self-promoter. And he’s mastered the art of “authenticity” — that combination of staged closeness, strategic imperfection and calculated self-deprecation that’s the key to charming the web.

Earlier generations of celebrities grew their fame exuding an aura of glamorous inaccessibility. Nash, however, has built his on distilling the utterly unremarkable into blink-and-you-missed-it clips, starring a seemingly available kid as matinee idol. He’s the good-looking class clown millions of girls dream of knowing. And, if they have a smartphone or an Internet connection, they can feel like Nash is their pal.

“He’s got all the right pieces in play at the right time,” said Jeff Hemsley, an associate professor at the University of Syracuse and author of Going Viral, which explores how ideas spread online. “And people love it. They share [his videos] over and over again.”

The whole boy-next-door persona can seem contrived among celebrities of a certain stature, but Nash genuinely gives off the impression of someone who’s still more 16-year-old kid than groomed child star. He favors Vans sneakers, enjoys crossing hallways by skateboard and has little overt interest in humoring reporters who might have flown in from New York to follow him around for a weekend. He’ll stay up late having a pillow fight in his hotel room, and get excited when he sees posters emblazoned with his name.

But Nash, of course, is not average. Nash is famous. As he ducked away from the screaming throngs at the mall, leaving them with nothing more of himself than the same digital images, an uncomfortable truth became clear: The closer you get to Nash, the farther you feel from him. On Vine, Nash can post a single video and make millions feel he’s talking directly to them. In person, you can feel lucky to get a full sentence. At the dinner table, waiting for his takeout, he stares at his phone. He slips easily into the clipped, non-committal generalities of the disinterested teen. (How much has your life changed since you started making Vines? “A lot. A lot.”) And he now has a PR company to manage who gets access to him. The most intimate moment most fans get to share with Nash is taking a selfie. All this raises a few questions: How precarious is stardom built on the mirage of a personal connection? Can Nash keep an aura of availability as his celebrity grows, or will he travel further out of reach, only to be replaced by a nearer star?

Nash is, after all, only the latest in a string of nobodies who’ve become sponsorable online somebodies by bypassing agents and taking their talents directly to the web. In its short life, Vine has spawned a suite of homegrown celebrities who are creeping toward six-figure salaries thanks to an exceptional — and exceptionally strange — talent that until now had little marketable value: the ability to capture attention with six-second bursts of humor or skill. They include Viners like

Like other Vine sensations, Nash hopes six seconds of fame will be the gateway to something more lasting than 15-minute stardom. He “isn’t really monetizing right now,” according to Alan Spiegel, one of Nash’s three managers including his father. Instead, having conquered the smartphone, Nash is going after larger screens that can put distance between an idol and his fans.

A year into his Vine venture, Nash has nixed his college plans and dropped lacrosse, which he once counted on as his ticket to a school like Princeton or Penn. His new dream, he said, is to be “the first, like, George Clooney or Leonardo DiCaprio who starts from the Internet.” According to the logic of a plucky teen who’s excelled at most of the things to which he’s set his mind, going Hollywood is, despite its risks, purely the most logical career route.

“You can play professional lacrosse, but they make less than a teacher’s salary now. I always thought about that. And it’s a very difficult career, a short career, as a pro athlete,” Nash explained. “I was like, ‘I can be an entertainer until I’m 75!’ So logistically, it seemed better. And I liked it better.”

Nash recently landed a deal to appear in a yet-to-be-specified movie produced by Dreamworks-owned AwesomenessTV and the director of Varsity Blues. This spring, Nash also moved out to Los Angeles with Cam, a Vine star and aspiring actor Nash met through the social media site, so the two teens could be closer to their agents at William Morris Endeavor. Nash’s father, Chad Grier, declined to share details about their new living arrangement, as the boys “are stalked on a fairly regular basis as it is.”

Depending on how you look at it, these milestones could be harbingers of future success — or evidence of how precarious six-second celebrity really is.

“There’s always someone coming, always someone funnier, cuter, more engaging, which is why [social media] stars today are seeking out professional managers and agents,” said Brian Solis, a digital analyst and anthropologist with the Altimeter Group, a research firm. “They have to fight for relevance. And they have to be able to monetize the popularity while they have it.”

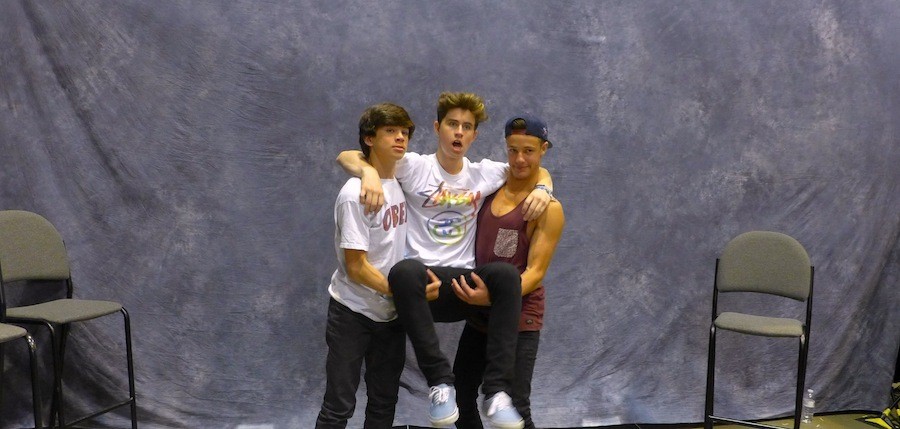

A few months ago, Nash flew to St. Louis to enjoy another new perk of fame that had come only recently: the ability to charge people to meet him in person. He, Hayes and Cam — Vine sensations with a few million followers each — were making their first appearance at Wizard World, a fan convention that seats its talent behind bouncers. For $150 plus tax, “VIPs” would get a photo with the guys, an autographed headshot and entry to a Q&A panel with the three Viners. The tickets — well over 500 in total — sold out.

On Friday, the group’s first day in Missouri, Nash showed up half an hour late to a radio interview. He was wearing sweatpants and a gray sweatshirt. “I can’t breathe,” whispered Julia, a 13-year-old fan, as Nash, Hayes and Cam approached the station. Julia had set up the talk radio appearance by messaging Nash’s father on every one of his social media accounts. As the trio entered, she rearranged her sweater and smoothed her hair. The guys shuffled past her, taking little notice. At someone’s urging, they turned around to pose for the obligatory photo, then settled themselves in a small circle with their backs to their fan. Julia stared at their huddle, but failed to elicit a reaction.

When he does open up, Nash can sound like a male Miley Cyrus who’s spent too much time with televangelist Joel Osteen. A great song is a “banger,” a babe is a “bae,” sketchy stuff is “ratchet” and Nash’s trademark expression (which, in fact, his managers would like to trademark) is “nashty.” In the next breath, Nash will say he is “so blessed” to have such loyal fans, and argue what’s holding back many Viners is the “filth” in their videos — more specifically, the “f-bombs,” “cuss words” and “racial stuff.” The Grier family attends what Nash’s father calls “rock ‘n roll church,” and Jesus Christ gets occasional shout-outs in Nash’s Vines. (Nash himself regularly consults a Bible app on his iPhone.)

Asked whether Nash’s faith has shaped his view of gay people or same-sex marriage, Chad Grier, answering on his son’s behalf, wrote in an email, “Nash believe [sic] in equal rights for all people,” but “is not a political buff nor does he wish to engage in politically charged debates especially when he is not very well educated on a particular issue.” Grier said of the HIV Vine that Nash “knows what he did was wrong,” and is “extremely sorry.” The video, he wrote, had been “aimed at entertaining [Nash’s] handful of friends/followers at the time who all thought sophomoric and inappropriate humor was funny. It’s not.”

The upbeat teen Nash plays on smartphone screens diverges so sharply from the kid who lashed out against “homos” that it can be hard to shake the sense his online image is at least in part a carefully constructed fiction — one more staged than his casual candids might suggest. Nash discusses “filth” in terms that hint he may consider it imprudent for business reasons: “You don’t want to come off as stupid. You don’t want to have racial slurs. You don’t want to limit yourself. You want an audience that [includes] anyone from 2 years old to 50 years old,” Nash said in an interview, before his controversial Vine had resurfaced. What does best for his audience, he added, is “anything that’s upbeat, anything that’s happy — nothing with like a bunch of profanity or anything bad in it.”

Nash’s father said his son wants to use his platform to “communicate positive messages and to support positive causes” — and not, presumably, to spread misinformation, as in the HIV vine. His decision matters: Audiences are so devoted to these online sensations that they’re likely to be influenced by whatever sentiments come through their screens. When Shawn Mendes, another teenage Vine star, launched his debut album and asked fans to “get this bad boy to No. 1,” it took them just 37 minutes to push it to the top slot on iTunes.

Vine’s most popular user almost ditched the service before he ever really got started. Nash said he posted a few videos to Vine shortly after it launched early last year. Then he deleted it along with every other social media app and canceled his phone’s data plan — a purge meant to help him focus on sports.

A few weeks later, he re-downloaded Vine at a teammate’s urging. This time around, his first video, “How to wake up like a thug,” got him 1,000 likes and 4,000 followers after it was shared by another Viner with a large following. “I was like, ‘Holy crap! I have to keep this up,’” Nash said. His second clip earned him thousands more fans. “And then I didn’t want it to stop,” he recalled. “I made Vine after Vine after Vine.” Nash used a Sharpie to scrawl “100,000” on his chest, thinking he’d make a video to try to get 100,000 fans. By the time he’d edited it to his satisfaction, he’d hit 130,000 followers. Then, Nash said, Vine “was, like, my life.”

Nash scrutinized the techniques of Vine stars like Marcus Johns, a college student with several million fans, for clues about what would draw the largest audience. Currently, the 12 most popular Viners are each variations on the same formula: They are all comedians, they are almost all men and many of them are God-fearing Christians who bleep f-bombs and steer clear of sex. Their videos also hum with a level of energy that can be exhausting in high doses. There is no filler or downtime, only punchlines and story climaxes in continuously looping six-second doses. “It’s fast, it’s punchy, it’s like a party,” said Hemsley, the expert on viral phenomena.

While Facebook can feel like the Wal-Mart of social networks — the brightly-lit social media superstore teeming with parents — Vine can evoke a basement rec room on a Friday night — young, frenetic and full of inside jokes. There are pretty girls filming staged sleepovers in one corner, someone belting out John Mayer somewhere else and everywhere, the attractive fraternities of male Viners who film “collabs” (collaborations) they use to help each other get more fans.

Nash realized from his study of Vine that the blockbuster formula had two ingredients: He had to be funny, and he had to be clean. On camera, his catchphrase is “You gotta bae? Or nah? You tryna dae? Or nah?” Off camera, it’s “don’t limit your audience.”

“I like being the center of attention,” Nash said matter-of-factly. “I want to be in the limelight, basically.”

Behind the apparent spontaneity of Nash’s videos is a shrewd creator who knows just what to feed social media. He’ll film his clips over and over again until nothing feels rushed, or spend hours on editing. Nash has an instinct for crafting short skits that go down easy in the din of the school bus or cafeteria, where his teenage fans inhale his videos. “Kids still want programming, but they don’t want to sit through Boy Meets World” — a mind-numbing 24 minutes long — said Rob Fishman, a former Huffington Post editor who is now the co-founder of Niche, a marketing platform that connects brands with social media creators, including Nash. “What Nash and these guys do is they fill that void.”

Knowing that videos take longer than text to load on Vine, Nash takes special care to give every clip a title that hooks viewers into waiting — vague, but just specific enough to set up the joke: “Hayes Grier is a little late” or “Looking through old pictures like…” or “I’m never making eggs again..” He also tries never, ever to publish videos in the middle of the day. He saves them for after 3:00 in the afternoon — just as teens are streaming out of school and pulling out their phones.

The artistry of Nash’s self-promotion sometimes seems to outshine the substance of the videos themselves. Other Vine stars might spend days perfecting their uploads, devising elaborate sets or creating ingenious stop-motion animations. For Nash, however, developing, planning and shooting an idea takes him “anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour.”

During a cab ride in St. Louis, Nash did all three between stoplights. He was flicking through his phone in the backseat and grumbling about how an obscure rap song he discovered on YouTube had hit iTunes’ top 10 list after he’d featured it in a Vine. And then — action!

“Make an awkward smile,” Nash directed Cam while the two sat squished together. Nash held his iPhone at arm’s length and started to record.

“I’m going to ease into it,” said Cam, a former model. He looked ahead, straight-faced. Then, slowly, Cam rotated his head toward the camera and bared his teeth. Awkward! They cracked up. Nash saved the clip.

He posted it two weeks later on his second Vine account — the less scripted “messing around” channel, “Nash Grier 2.” It wasn’t up to the standards of his main feed, he explained later, where each video “has to entertain everyone.”

“I want the reputation that if Nash did it, it’s going to be perfect,” he said.

Photo by Heather Marie Photography

Nash has a tendency to fixate on the things he’s passionate about, at times to the exclusion of just about anything else.

When he was in middle school, football was everything. Nash worked toward a dream of becoming a “Super Bowl MVP NFL quarterback” by setting up drills for himself in the backyard, his father said. Nash would force himself to run laps around the family’s two-acre property, or sprint through old tires he arranged on the lawn.

Then, it was lacrosse. Chad Grier said he watched his son spend hours after school practicing alone with a lacrosse stick and a bucket of balls. Vine replaced lacrosse. And now, Nash says he’s “trying to steer away from being called a Viner.” He’s prioritized YouTube videos and auditions in Los Angeles as he works to reinvent himself as a Hollywood star.

As Nash describes it, it’s not that he suffers from a short attention span, so much as he’s driven to pursue anything that’s hard to get. “I’m in school a lot less. Everyone’s like, ‘Oh, that’s a big risk for a kid who’s making videos on the Internet,’” said the teen, who’s taking his high school courses online. “When people say ‘that’s risky’ or when the odds are not in my favor, I’m more motivated than ever.”

It’s his fans who may be easily distracted. It’s true that other, less popular Viners have already leveraged social media stardom to secure more traditional media deals. The singers Us the Duo, for example, scored a record contract, and Brittany Furlan, a comedian, is developing a TV show. Yet some half-dozen comedians have cycled through the top spots on Vine since its debut. And as Furlan told TheWrap, “[T]he lifespan of people on Vine is short.” Nash’s slurs haven’t so far led to mass boycotts of his Vines — “He didn’t really know what he was doing, he was a teenage boy,” said one girl, whose friends have also stayed loyal — but the rate at which he’s adding new followers has fallen by half since the beginning of the year, according to marketing platform Niche.

The Griers are also on a steep learning curve. Chad Grier recently quit his job selling IT software to help run 26MGMT, a management company focusing on Vine stars that counts Nash, Cam and Hayes among its five clients. A former quarterback, Grier is also the football coach at Nash’s private school and trained another one of his sons, Will, who was recently recruited by the University of Florida Gators. Nash’s mother works distributing vitamin products, and his stepmother juggles several part-time jobs.

Nash has taught himself most of what he knows about making videos for the Internet. His film studies started on a Mac computer in the family’s living room, where he used Apple’s free Photo Booth software to direct short films starring him and his brothers. More recently, using money he earned plugging Sonic milkshakes and Virgin cell phone plans on Vine, Nash bought himself a camera and video-editing software that he learned to use by watching tutorials on YouTube. He also manages all his own social media accounts, and has been savvier than most Viners about spreading his followers from Vine to Twitter to Instagram to YouTube to Snapchat. (Nash also encourages his fans to follow him on Mobli, a social media startup with which he has an endorsement deal.) In the span of a few hours, he’ll coach his brother on wooing fans — “Dude, you’ve got to get better at answering questions” — and counsel his dad on his wardrobe needs.

“Failure,” Nash said, “that’s my biggest fear.”

At one point during the weekend, Chad Grier leaned over Nash’s shoulder to admire a photo he had taken while skateboarding around the St. Louis Arch. Nash had angled the picture so that his feet appeared to be on either side of the landmark, and he planned to post it on Instagram.

“That’s an artsy black and white picture!” Grier said.

“Actually, it’s not black and white,” Nash corrected him. “It’s actually a vignette with negative saturation.”

By Saturday morning of Wizard World, Nash’s hotel had come to resemble a refugee camp for well-dressed teenage girls. Fans camped out on the floors where Nash’s managers had rented rooms, hoping for a glimpse of the Vine stars as they exited the hotel. No luck: The guys were whisked downstairs through the service elevator into a black Escalade waiting below.

During their drive, Cam gawked at Wizard World attendees in Star Wars outfits, and remarked he could “have a fucking field day messing with people.”

Nash punched him.

“No! We’re not playing right now!” Cam protested

“Oh, we’re not playin’ right now. It’s not a game,” Nash said, lilting his voice to make it clear “not playin'” meant “not foolin’ around.” He clarified, for the uninitiated, that the guys have a no-filth challenge: “We play this game: Whenever someone cusses, they get a smack.”

The boys were deposited at a concrete hangar by the convention center, and Nash installed himself behind a table flanked by security. Facing him were throngs of squirming teens corralled behind metal guardrails.

“Will you marry me?” a “VIP” asked the 16-year-old with a ring pop as she filed by to claim one of his autographed headshots.

This was the closest most of the girls had ever been to their idol. But thanks to the stream-of-consciousness updates Nash dispatches online (“I LOVE ACNE. YES. WOO.”), his fans have the sense they know every detail about his daily routine.

“He just got highlights,” one said with authority. Another: “What’s that water that Nash endorses? … Yeah, I bought it.” A third girl confessed, “I Google-earthed their house.”

Nash has worked hard to manufacture that unique sense of imitation-intimacy that’s only really possible online, where “likes” are easily conflated with love. He knows a noticed fan is a loyal fan, and in St. Louis, he filled empty moments in the car or in line at the skatepark currying favor with followers by “liking” their Instagram photos and replying to their tweets. Nash’s devoted work ethic is both admirable and off-putting, betraying, as it does, the sense he’s ignoring humans around him to flatter adoring strangers online, all at his own convenience and discretion. During a brief break from signing photos, he stood behind a black curtain in a makeshift waiting area answering his fans’ tweets.

“I favorite them and they freak out,” he explained. It was difficult to hear him. A few feet away, there were hundreds of real-life fans, all freaking out.

Julia, the teen from the radio station, was among the girls waiting for a turn to see Nash. She used to like One Direction, she said, but now prefers the Vine guys “because they’re so much more real.”

“You can relate to them. You have a chance of being followed by them on Twitter or Instagram. But with One Direction, it’s like, no way,” said Julia. She counts Hayes among her Twitter followers and gets alerts on her iPhone each time one of her Vine idols tweets.

“One Direction sings and that’s great,” agreed her friend, who’d brought a piece of jewelry as a gift for Nash’s stepmother. “But with these guys, you feel like you could actually have a conversation with them. They wouldn’t be stuck up or stuff like that.”

At the receiving line, Nash was mute and all business. Sign a headshot, slide fan’s proffered gift under the tablecloth, mug for a selfie, repeat. In one 15-minute stretch, he broke his silence only to exclaim that the ink had smudged on one of his signatures.

Finally, it was Julia’s turn. She held out a picture of Nash, which was affixed with a Post-It note on which she’d been made to write her name in order to expedite the autograph. Julia bounced from her left foot to her right. Nash consulted the Post-It for the name of the person to whom he should dedicate the photograph — “Julia” — and bent over his Sharpie.

“Do you remember me?” Julia asked.

Nash looked up at her for a moment before returning to the photo, where he scrawled what in another lifetime might have been a yearbook inscription: “Julia ♥ I love you!!! You’re the best.”

“I remember your face,” he said. “But I don’t remember your name.”

After six hours of signing photos and posing for pictures, the three Viners were released. That night, while the guys were at a skateboard park blowing off steam, packs of teen girls milled about the lobby of the hotel. It was past 10 p.m., and the girls were still huddled together — most standing away from their parents, some hugging under blankets in the cool spring air, others loitering around the Outback Steakhouse where Nash, Hayes and Cam had eaten the night before.

A high school soccer team was staying at the hotel as well, and the boys, all around the girls’ age, stood equidistant from each of the female groups, darting glances in their direction. There was no mingling. The girls checked their phones, bringing up Instagram photographs of the boys they wanted so desperately to see in real life. The members of the soccer team looked confused.

That night, Julia’s friend, who’d been perplexed by Nash’s aloofness earlier in the day, shared some big news in a text message: “Nash followed me on Twitter!” she wrote. “I’m so happy!”

With the press of a button, all was forgiven. Nash was back to being the teen heartthrob — digital, but lovable again.