“I HAVE NO SPOILERS, NO FLAPS, NO ELEVATORS AND IF I RUN THIS THING DRY, NO REVERSE THRUST!!!”

Nicolas Cage, panicked and bug-eyed, is once again fighting to avert disaster on the big screen, this time as airline pilot Rayford Steele. Fire spews out of a gash in the plane’s wing; a chisel-jawed young man attempts to subdue an unruly mob of passengers as a blonde flight attendant is tossed about in her seat. On the ground, cars crash, explosions rock the sky and civilization is engulfed in a wave of panic and anarchy.

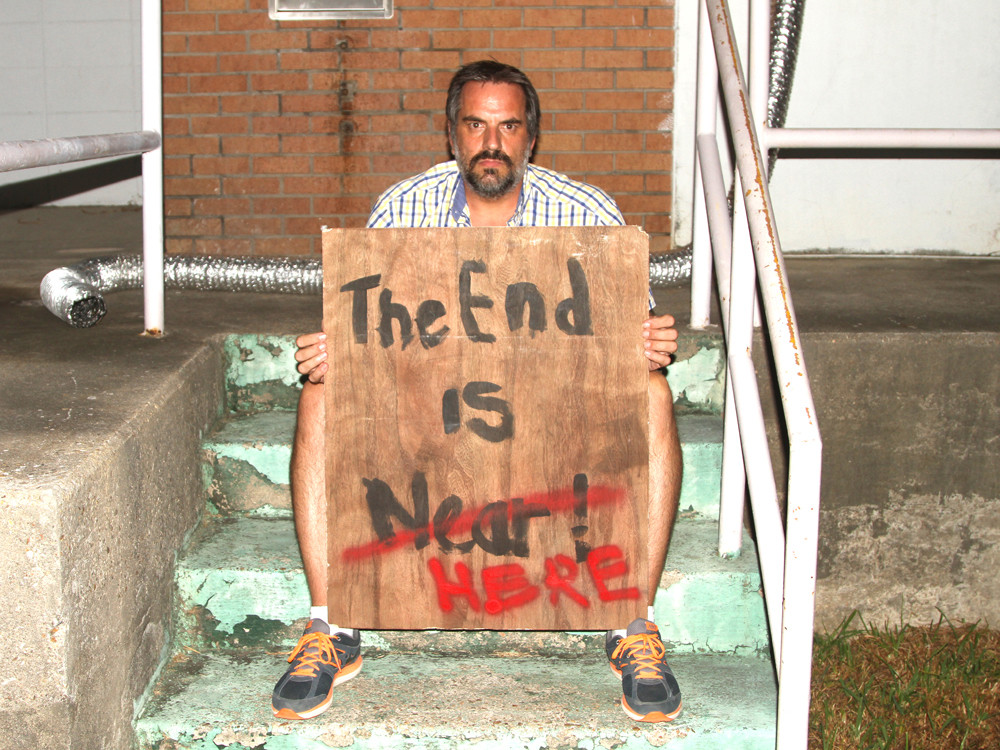

“Looks like the end of the world,” a man remarks.

What it looks like is typical Hollywood apocalypse porn in the vein of “Deep Impact,” “The Day After Tomorrow” or “2012.” In this case, however, the end-times event isn’t a giant asteroid, catastrophic climate change or a Mayan prophecy come true, but the Rapture, with non-believers abandoned to fend for themselves after Christ’s true followers are beamed up to heaven. Based on the series of books by the same name, which were written by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins and have sold over 65 million copies since 1995, “Left Behind” delivers all the titillation and destruction we’ve come to expect from a Hollywood blockbuster.

Yet, despite its A-list razzle dazzle, “Left Behind” was produced outside of Hollywood’s traditional orbit. The man primarily responsible for bringing it to the big screen is Paul Lalonde, a Canadian filmmaker who co-produced and co-wrote it. His Ontario-based production company, Stoney Lake Entertainment, is part of an emerging nexus of movie studios that are devoted to creating Christian films.

Movie-making may be synonymous with Los Angeles, but the Christian film industry is scattered across North America. There’s Pure Flix Entertainment in Scottsdale, Arizona, Kendrick Brothers Productions in Albany, Georgia, and Five & Two Pictures in Nashville, Tennessee. Culture warriors no less prominent than Glenn Beck and Rick Santorum are trying their hands at film production as well. Santorum, a former Pennsylvania senator and GOP presidential candidate, became the CEO of EchoLight Studios, in Franklin, Tennessee, in 2013. Earlier this year, Beck announced that he had started renovating a 72,000-square-foot studio in Irving, Texas, which he plans to use for film production.

“I’m much more into culture than I am into politics,” the former Fox News host said at the time, “and that’s where I intend on making my stand.”

For decades, Christian films were defined as much by their shoddy, low-budget production values as by their religious themes and agendas. “Christian movies have historically meant very bad movies,” Lalonde said in an interview, “and I can say that as a guy who made some of them.”

“Left Behind,” by contrast, was produced and marketed to the tune of $31 million. It premieres Friday on 1,750 movie screens around the country. Lalonde hopes it will reach not just a churchgoing audience, but a secular one as well.

“You were just preaching to the choir, which was great, because the choir loved them and we were having fun doing them,” Lalonde said of earlier Christian films, “but they never really broke beyond the Christian audience, and that was something I always wanted to do.”

The premiere of “Left Behind” is poised to be a watershed moment for the Christian film industry. Not since Mel Gibson’s 2004 hit, “The Passion of the Christ,” has there been an independent Christian film with a budget comparable to those of Hollywood studio productions. And unlike “Passion,” “Left Behind” has a marquee star attached.

While show business is fickle, and the success of “Left Behind” is far from guaranteed, it certainly won’t be the last religious movie aiming to score big. Christian filmmakers now have the skills, tools and infrastructure necessary to produce more sophisticated films, and they hope to reach beyond their core fans to a larger, less devout audience. After years in the wilderness, they are finally a force to be reckoned with.

Jesus is ready for His closeup.

For Lalonde, 53, “Left Behind” represents the culmination of a decades-long career spent outside the Hollywood establishment — a career that in many ways mirrors the Christian film industry’s rise from creative and cultural obscurity.

He got his start in the late 1980s marketing short films and documentaries on his weekly Canadian television show, “This Week In Bible Prophecy,” which he co-hosted with his brother Peter. The Lalondes shot their first short film, set during the Rapture, in their office and cast their receptionist in one of the main roles. Another character “walked in and saw she was gone, but her clothes were still there,” Lalonde recalled.

The production values may have stunk, but the video turned into a hit. In 1995, the Lalondes founded their first studio, Cloud Ten Pictures, to help create and promote their films. In 1998, they were able to parlay the modest proceeds of their shorts and documentaries into their first feature-length film, “Apocalypse.” Unable to afford union actors, the brothers cast a host from a Canadian home shopping channel as the lead.

“He would sell Ginsu knives by day and shoot our movie at night,” Lalonde said. “We made this movie for $200,000, and it looked like a movie made for $200,000.”

In 2000, they produced a straight-to-DVD version of “Left Behind,” and followed it up with two sequels, aiming to capitalize on the books’ popularity. Though the films did well within their niche market, they never caught on with a wider audience.

Hollywood didn’t pay much attention to Christian films until 2004, when Gibson released “Passion,” his crucifixion-as-slasher flick. The major studios had all passed on the project, so Gibson and his production company spent an estimated $45 million to make and market the film themselves, and they promoted it through churches and religious leaders. The response was overwhelming. “Passion” grossed $600 million at the box office and became the most lucrative R-rated movie in cinematic history.

That opened Hollywood executives’ eyes to the mainstream potential of Christian films. “You can’t ignore those numbers,” Mark Johnson, a prominent film producer, told The New York Times in 2004. “You can’t say it’s just a fluke. There’s something to be read here.”

Over the past decade, Hollywood studios have tried to replicate the success of “Passion” with films like “Amazing Grace,” “The Book of Eli,” and the “Narnia” trilogy, which Johnson produced. But those films represent just a small fraction of Hollywood’s overall output. These days, the film industry depends largely on foreign box office proceeds, and studios have focused on films with universal appeal — resulting in endless revamps of movies like “Transformers” and “Iron Man.”

Christian viewers haven’t exactly responded enthusiastically to the films Hollywood studios have produced for them, saying they watered down theology or misrepresented it entirely.

Religious audiences directed a great deal of scorn at this year’s Old Testament thriller, “Noah” — so much so that an ill-informed onlooker might assume that outspoken atheist Richard Dawkins had been cast in the titular role. Glenn Beck derisively called the movie “Babylonian Chainsaw Massacre.” The film’s domestic gross was around $100 million.

studio in Texas. (Photo: Rob Kim/Getty Images)

“If it was biblical, it would have made $400 million,” said veteran Christian filmmaker Dave Christiano. “But because they messed around and made an un-biblical movie, the churches passed on it.”

Kevin Sorbo, who is best known for playing the beefcake title character on the TV series “Hercules,” has starred in a number Christian films, including the recent hit “God’s Not Dead.” He says Hollywood remains disconnected from the Christian film industry’s primary targets, who live “between California and New York.”

“I don’t think Hollywood does it on purpose,” Sorbo said. “I just don’t think they understand their audience.”

Beck has been more pointed in his critique of the mainstream movie industry. “Hollywood is missing this moment to reconnect with the American people because they don’t speak the language,” he told The Hollywood Reporter in April. “Some of it is out of spite — they might not like people of faith.”

In the past decade, Christian filmmakers have stopped waiting for a second coming of “Christ.” Instead, they’ve used their own studios and production companies to push out a torrent of movies themselves. The last three films from Kendrick Brothers Productions alone have grossed a total of over $75 million at the box office, despite running on a fraction of the screens typically reserved for major studio films.

Recent movies like “Courageous,” “God’s Not Dead” and “The Son of God” are proof of the new system’s potency. Each was produced for under $5 million and grossed tens of millions of dollars — a result that would be impressive for any independent movie, Christian or not. “Facing the Giants,” about an underdog high school football team, was a particularly successful effort. Made for a paltry $100,000, the film grossed $10 million.

And whereas prior Christian films resembled the Lalondes’ earliest efforts, with boom mics seeming to make as many cameos as the filmmakers’ families, today’s Christian movies increasingly look like their mainstream counterparts. While they can’t boast the bloated budgets of Hollywood’s biggest franchises — or even the $31 million spent on “Left Behind” — technological advances have allowed filmmakers to produce quality films on relatively small budgets. Social media has also allowed Christian filmmakers to successfully promote their work without the massive marketing budgets of mainstream films.

The rise of Christian film studios comes with heightened expectations, however. Like traditional Hollywood studios, their backers aren’t philanthropists. They want to see a profit. That means angling for as big an audience as possible. And given the increased competition, Christian film purveyors predict that simply making films with religious messages will not be enough.

“I think securing funding for faith films based on the message will become more difficult,” said Kyle Idleman, a pastor at Southern Christian Church in Louisville, Kentucky, whose City on a Hill Productions was behind “The Song,” released last week and produced for under $3 million.

“It was exciting and felt a little bit novel initially, but it is show business,” Idleman said. “You’ve got to be able to have a viable business model if you want to keep doing it.”

While some movies still serve up their Jesus in great, heaping dollops, many of today’s faith-based films are more sparing. There are thrillers, romantic comedies, dramas — movies aimed at every possible subset of the filmgoing public. Websites like Christian Film Database enable visitors to browse movies by subject, such as Heaven, Hell and Bible History, and genre, like Adventure, Horror and Sci-Fi.

“Moms’ Night Out,” for example, is a milquetoast, PG caper about a group of mothers just trying to let loose while having to deal with incompetent babysitters and aloof husbands. Or, for younger audiences, there’s “Believe Me,” a raunchy, Judd Apatow-ish comedy — replete with towel-whipping banter, an indie rock soundtrack and a cameo by no less a paragon of bro-dom than Nick Offerman. It could just as easily entertain a stoned 17-year-old looking for a chuckle as it could an abstentious student at Bible college.

Christian filmmakers “are creating a connection to religion that is not immediately recognized by a viewer as an attempt to proselytize,” said Jeanine Basinger, professor of film history at Wesleyan University. “They’re folding the message in, they’re learning to make subtext more powerful, and thus they’re becoming better propagandists.”

Though not all of today’s Christian films succeed in their attempts to fuse salvation and entertainment, their producers recognize the need to make films that aren’t overbearing morality tales. “There is a tendency among faith films to sanitize the story, and I don’t think that’s consistent with Scripture,” said Idleman, who believes the Bible is as much a source of romance, drama and action as any comic book. “There are a lot of broken stories in the Bible,” he said.

Ultimately, said George Escobar, a Christian filmmaker and educator, there’s an audience for Christian films of every stripe. “There’s a spectrum, and different audiences are going to gravitate to different ones,” he said. “I think it’s healthy. People are in different stages in their walk.”

Chantilly, Virginia, situated on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., isn’t exactly a hotbed of creativity and culture. Mostly empty and sterile, it’s dotted with prefab cul-de-sacs, mid-range retail stores and several shopping malls. There are no art house theaters, and unless the next installment of “The Expendables” takes a decidedly avant-garde turn, the local cineplex likely won’t be screening any indie films in the near future.

But it was in a nondescript office complex in Chantilly that Escobar held his annual two-day Christian filmmaking workshop for about a dozen students who had each paid $199 to be there. They were a surprisingly diverse bunch, hailing from locales as far away as Indiana and culturally distant as Brooklyn. Some were neophytes hoping to get into the industry, while others were practiced filmmakers looking to hone their craft. One young attendee, set to start college soon, was being chaperoned by her mother.

The workshop, held in June, took place in the joint offices of Advent Film Group, a Christian studio that Escobar co-founded, and World Net Daily Films, the documentary filmmaking arm of far-right conservative news outlet World Net Daily.

Escobar, friendly and soft-spoken, with a kind, round face, exhibited none of the pretensions of a stereotypical director. If it weren’t for the cameras, tripods and film rigs scattered about the room, one might easily mistake the class for a get-rich-quick seminar or an LSAT prep course.

Filmmaking is the Lord’s work, Escobar began, even if the movie business is dominated by unbelievers and purveyors of obscenity. To make his point, he read aloud a passage from the Book of Numbers, in which God instructed Moses and the Israelites to scout and settle the Promised Land. Then, with a click of his mouse, the text on the projector changed and Escobar read an altered version of the scripture.

“[The Lord said,] ‘So send some craftsmen to explore Hollywood, which I am giving to believers from each discipline: writers, actors, directors, cinematographers and more,'” he read. “So at the Lord’s command they went out to the vast wasteland of culture. God said to explore moviemaking, go up through California on into the hills of Hollywood.

“[The Israelites said,] ‘We went into the land called Tinsel Town, and it does flow with fame and money, and here is its fruit,'” he continued. “‘But the people there are powerful and their movies are full of stars and are very expensive. We even saw descendants of Spielberg there.'”

Some of the attendees chuckled at Escobar’s revised scripture, but most listened with rapt attention and took notes.

The Lord, Escobar said, was commissioning Christian filmmakers to go out and spread the word and had provisioned them with the means to do so. The size and strength of the establishment shouldn’t intimidate them, he added, because God was greater than anything they faced.

“Instead of pursuing your stories, figure out what stories God wants told,” he said. “The ones that He wants told will probably get funded. It’s pretty simple!”

And the Lord isn’t just a guiding light, according to Escobar. He permeates every aspect of production: He outlines the script, secures funding, blocks scenes and makes casting decisions. He probably decides whether there are too many danishes at the craft services table.

Escobar recalled a moment during the shooting of “Alone Yet Not Alone,” a film he released last year, when he and one of the lead actresses reached an important juncture in the script and were unsure of how to proceed.

“She and I, we just stepped off the set for a moment and we started to pray, ‘Lord, we’re not really sure what you want us to do,'” Escobar told his students, “and then it was plainly obvious what would Christ do in that moment.”

One student at the workshop urged the others to join the Hollywood Prayer Network, an organization dedicated to improving the movie industry through prayer. Several spoke of films’ “Kingdom” returns — the profits their filmmakers would reap in heaven — as opposed to financial ones. Discussions of whether secular films like “The Blind Side” were Christlike were common.

Indeed, it’s films like “The Blind Side,” with its family-centric morality and uplifting message, that Escobar hopes to emulate, though perhaps with more religion thrown in the mix. The classic 1981 film “Chariots of Fire,” which positively portrayed a Scottish missionary who sought to use his talents as a runner to glorify God, is another such film. “We can make something like that,” Escobar told his students. “It’s been done, and it’s something I aspire to.”

According to Escobar, over 1,000 students have attended his workshops since he began teaching them in 2009. Only 10 of them have gone on to careers as full-time Christian filmmakers, yet he is nonetheless encouraged by the numbers, as they represent a new generation of Christian filmmakers with the technical expertise to produce films of a quality comparable to Hollywood directors.

Escobar, who immigrated to the U.S. from the Philippines in 1970, when he was 10 years old, spent most of his career developing video technologies for internet and telecom corporations. He was introduced to the world of Christian films in late 2006, after a screening of “Facing the Giants.” The film’s co-writer, Stephen Kendrick, an assistant pastor at Sherwood Baptist Church in Georgia, asked him, “George, with all the gifts that the Lord has given you, what are you doing about it?” Escobar recalled.

Three months later, he founded Advent Film Group. In short order, he’d raised $300,000 for his first feature film, “Come What May,” about a group of college students who challenge the Roe v. Wade decision in a moot court. The film went straight to DVD in 2009, and Escobar estimates that over 3 million people have seen it, thanks in large part to church screenings. Escobar went on to make three documentaries for WMD films, where he serves as vice president.

His work gained notoriety earlier this year when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences rescinded the Best Song Oscar nomination “Alone Yet Not Alone” had received. The Academy made the decision after the songwriter, Bruce Broughton, directly lobbied its members, which is prohibited. Still, conservatives revolted, claiming the decision highlighted Hollywood’s liberal bias.

Escobar was happy for the publicity and even happier that his new career was taking off. He was “finally being of use to the Lord.”

Through the mid-20th century, Hollywood’s output was less at odds with the tastes and sensibility of the religious and political right. Though the major film studios were by no means the right’s allies — conservative politicians, activists and clergy often found fault with films’ content and clashed with studios during episodes like the Red Scare — the major motion pictures of the day were far less risque than they are today.

Many faith-based filmmakers, including Escobar, speak reverently of the Motion Picture Production Code, a set of self-censorship guidelines first agreed upon by Hollywood’s major film studios in 1930. The code prohibited the portrayal of nudity and sexual relations, depictions of interracial or same-sex relationships and the mocking of the clergy. References to “God” or “Jesus” were permitted only in religious contexts, and criticism of the government was strongly cautioned against. The code demanded that scenes in bedrooms “be governed by good taste and delicacy,” forbade suggestive dancing and banned kisses lasting longer than three seconds.

“People talk about the Golden Age of Hollywood, and the kinds of films that were being made were largely informed by a Judeo-Christian culture,” said Escobar. “As a filmmaker, you may not be a believer, but you couldn’t escape that environment and culture. What’s happened is you get remakes of some of these films nowadays, and the Judeo-Christian values are removed and replaced by other, more secular philosophies.”

This was the gee-willikers Hollywood: The Hollywood of sentimental auteurs like Frank Capra, the pro-military Hollywood of the “Why We Fight” series and the Hollywood that counted Republicans like John Wayne, George Murphy and Ronald Reagan among its ranks.

“Movies became more conservative with the growth of the studio system, not more radical,” said Steve Ross, professor of history at the University of Southern California and author of “Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics.”

Films also reflected the greater religiosity of the age, specifically Christian religiosity.

“If you look at a movie [made] during the war, the beleaguered homefront people go to church on Sunday, and the minister speaks to them about their values and war,” noted Basinger, the Wesleyan film historian. “They were assuming an audience of Christians — not Buddhists, not Jews, but Christians.”

The industry was not immune to the cultural and political upheavals of the 1960s, however. The popularization of television and the proliferation of racier foreign films from the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and Ingmar Bergman forced the major studios to produce edgier material. Capra’s code-era films were soon being derided as “Capracorn.” The code was ultimately abandoned in 1968, and films like “Easy Rider,” “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Graduate” soon came to define the New Hollywood. Conservative stars grew scarcer, and liberal actors like Warren Beatty and Harry Belafonte set the stage for the A-list progressive activists of today, like George Clooney and Sean Penn.

Christian filmmakers failed to compete in a post-code, pre-VHS world where movie theaters remained the primary means of film distribution. Outside of church basements and the occasional Sunday morning TV movie, there wasn’t much space for low-budget productions of “Pilgrim’s Progress” and dry biopics about prominent missionaries. Christian-friendly stars like Pat Boone weren’t going to sell as many tickets as Robert Redford.

A Christian counterrevolution to the New Hollywood never materialized. Until now.

Back at the workshop, between discussions about casting, blocking and story arcs, hot-button political issues like gay marriage, school curriculums and parental notification laws kept cropping up. During a presentation on story development, Escobar extemporized a pitch about a woman who is forced to shut down her bakery because she refuses to follow laws antithetical to her beliefs. The woman ultimately decides to run for Congress.

Even as more and more Christian filmmakers aim to reach mainstream audiences, the politics of the far right remain ever-present in their work. That connection has only intensified in recent years, as religious and political activists have tried to leverage the emotional power of film.

“Since my time in politics I’ve noticed that entertainment has a huge impact on the country and therefore the government,” Rick Santorum told Time magazine last November, shortly after signing on to lead EchoLight Studios. “I always paid fairly close attention to those things and always felt like a lot of the things that I stand for are not necessarily talked about in a lot of films.”

in 2013. (Photo: Robin Marchant/Getty Images)

His studio is currently producing a movie centered around the Supreme Court’s recent Hobby Lobby ruling, which found that religious employers cannot be required to pay for insurance coverage of contraception for their employees.

Other Christian films similarly take their cues from current political debates. “Accidental Activist,” produced by the American Family Council, tells the story of a man ostracized by his community for signing a petition opposing same-sex marriage. The anti-abortion “Sarah’s Choice” follows an up-and-coming account executive who grapples with an unwanted pregnancy. And “A Matter of Faith,” premiering this month, features a college freshman who weighs the merits of her biology professor’s teachings on evolution against her own Christian faith.

“You’ve probably heard the term that culture is upstream from politics,” said Escobar. “Yes, I think it has an impact. You look at ‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington’ today and it’s [still] highly contemporary.” His own anti-abortion film, “Come What May,” was filmed with the support of Patrick Henry College, the small evangelical school in Virginia where the film is set. Anti-abortion organizations and other special interest groups held screenings of it after its 2009 release.

Escobar advised his students to align themselves “with an established organization with like-mindedness of purpose and shared viewpoint” — an arrangement that would ideally lead to “shared resources.” Moreover, he noted, such organizations “have pre-existing communications and sales channels to their constituents.”

During a Q&A session, one student screened a trailer for “Wait Till It’s Free,” a documentary he co-produced about Obamacare.

Escobar’s eyes lit up. There still hasn’t been a dramatization of Obamacare, he noted. “That’s something you guys need to expose.”

Hollywood has produced an endless supply of movies with menacing avatars for all things conservative, whether in the guise of prudish parents, corrupt Republican politicians or religious zealots. And just like their mainstream counterparts, Christian filmmakers have no shortage of material from which to draw.

But aggressive agendas, both political and religious, present a challenge for the Christian film industry as it attempts to capture a greater share of the secular moviegoing public. Critics have bristled at the genre’s more overtly religious hits. None of the top-grossing Christian films from the past decade have earned positive ratings on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes.

Indeed, the preachiness of the films can make the act of paying $11 for a ticket feel like tithing. For the non-devout, the only redeeming value is the occasional appearance by a star of yesteryear. (“Is that the dad from ‘Family Matters?'” “Hey, it’s the judge from ‘Night Court!'” “… Jon Lovitz?”)

Christian filmmakers know that churchgoers still represent the core of their audience. Even in trying to appeal to the mainstream, they don’t want to repeat the mistakes Hollywood studios have made in the past, on films like “Noah” and the “Narnia” franchise, and lose their devout fans in the process.

The marketers of “Left Behind” are hedging their bets, heavily promoting the film to conservative Christians and hoping the film’s explosions and Cage’s name on the marquee will attract everyone else.

They’re also encouraging religious fans to go see the movie with their more secular friends. In a recent promotional video for the film, “Duck Dynasty” star Willie Robertson declares, “Opening the door to unbelievers has never been this much fun.”

But the new generation of Christian filmmakers understands that fun — more than faith — is the operative word. At the end of the day, moviegoers just want to be entertained. That doesn’t mean filmmakers will have to completely cast aside their scruples and make “2 Fast 2 Jesus” or “Harold and Kumar Go to Church,” but finding a middle ground between entertainment and proselytizing will be key.

“To put an agenda before a story is part of the reason why you don’t see Christian films getting as good of ratings on Rotten Tomatoes or from critics or being nominated for Academy Awards,” said Will Bakke, the director of “Believe Me” and two documentaries on Christianity in the modern world. “They might as well just be sermons. You could even call it propaganda if you wanted.”

“For a long time after ‘Passion,’ everyone said they had the next ‘Passion,'” Lalonde said. But he thinks Christian filmmakers have been too myopic in their approach, forgetting that there is a “world outside the church.”

“They love Jesus, and that’s a wonderful thing,” he said. “But there’s a difference between making a movie for people who need to see it versus a film for people who want to see it.”