On September 9, 1966, Life magazine featured a story on Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr., the rising boxing star who’d recently changed his name to a moniker more familiar to sports devotees — Muhammad Ali.

At this point, Ali had already won the gold medal at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome and snatched the heavyweight title from Sonny Liston in 1964. He’d also become a point of controversy for fans following the champion. Questioned about his connection to Black Muslim leaders like Malcom X, and his conscientious objection to the Vietnam War, Ali was fighting battles in and out of the ring.

Untitled, Miami, Florida, 1970, ©Gordon Parks Foundation

“Those Vietcongs are not attacking me,” he declared when he resisted military draft, citing his newly adopted religion. “All I know is that they are considered Asiatic black people, and I don’t have no fight with black people.” In reality that stance, coupled with his over-confident and impetuous persona, made him all the more an icon in Civil Rights-era America.

The Life photo shoot of ’66 introduced Ali to Gordon Parks, a Kansas-born photographer who, with no formal training, made his way from photojournalist with the Farm Security Administration to the first African American staff photographer at Life magazine. Parks had previously turned his lens onto migrant workers and sixties activists. Now he was photographing “The Greatest.”

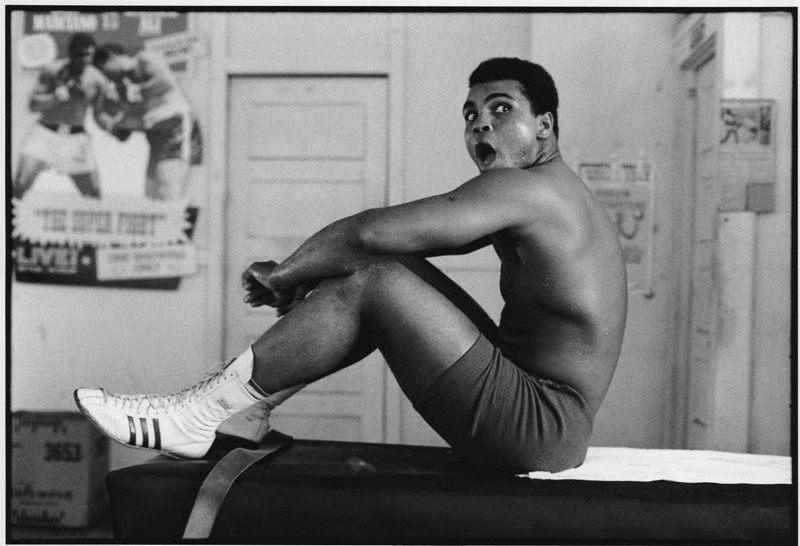

Muhammad Ali Grimaces at Photographers, Miami, Florida 1970, ©Gordon Parks Foundation American Champion portfolio

Parks traveled from Miami to London, snapping portraits of Ali as he puffed his chest out at reporters before his duel with Henry Cooper, and recoiled back into a patient, concerned individual when it was all said and done. Over several months, Parks and Ali forged a bond that no doubt affected the shots included in the magazine. Over time, Parks had found a way to reconcile the differences between himself and the boxer, and appreciate Ali’s place in the cultural pantheon. “At last, he seemed fully aware of the kind of behavior that brings respect,” Parks wrote at the end of his Life essay accompanying the photos. “Already a brilliant fighter, there was hope now that he might become a champion everyone could look up to.”

The article was called “The Redemption of the Champion.”

Parks’ work was instrumental in bringing the man of butterflies and bees back into the public’s lap, particularly the close-up photo of a sweat-soaked Ali staring wistfully beyond the camera after a training session. “For once, it’s a portrait of the champion without any hint of braggadocio,” The Guardian’s picture editor Jonny Weeks wrote. Four years after their initial meeting, the photographer returned to Ali’s side, profiling him once again as he prepared to fight Joe Frazier in 1970. Ali was still controversial and Parks was still sympathetic to the human behind the hero. The epigraph for that essay read: “Dripping with controversy, Muhammad Ali comes back.”

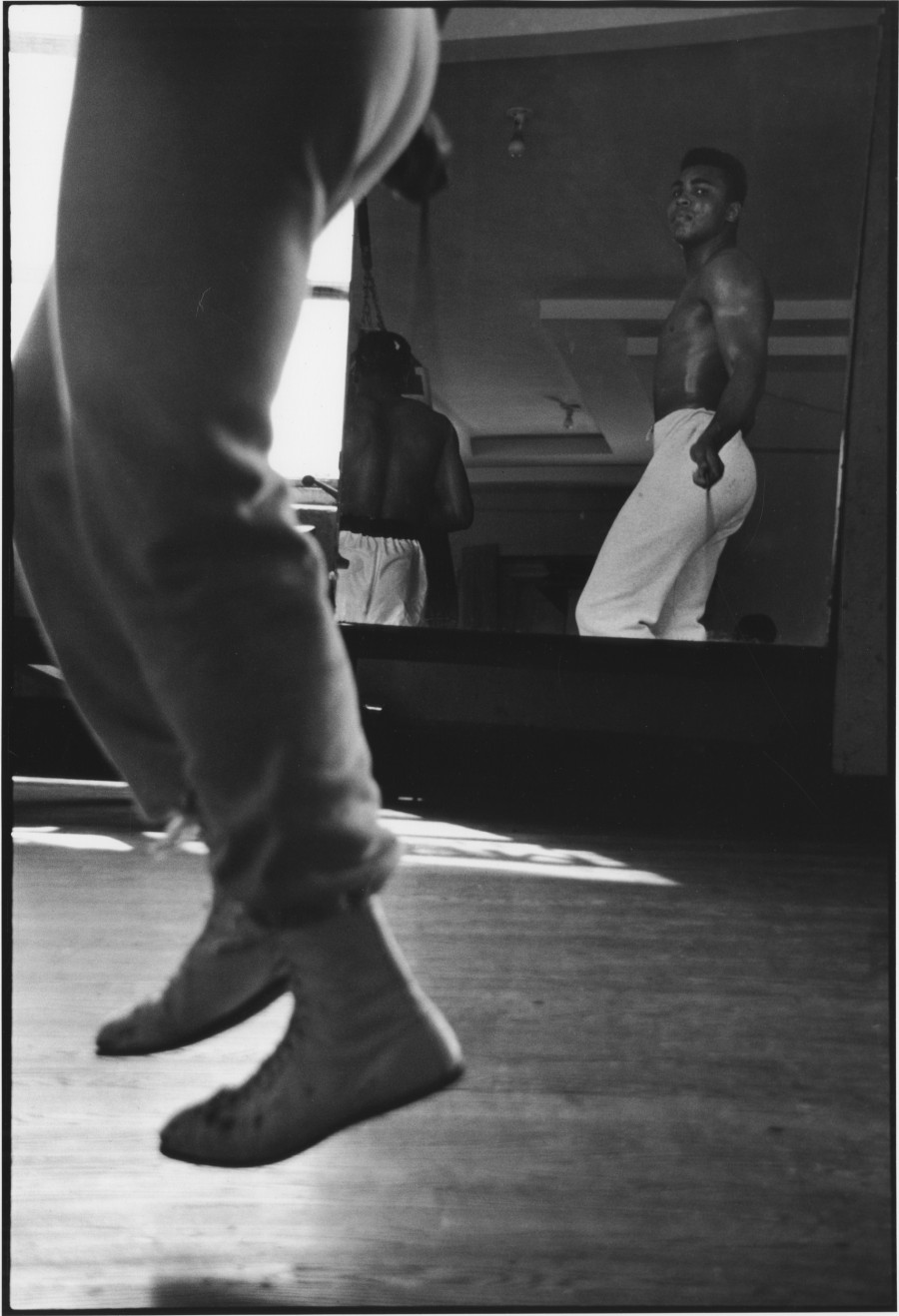

Untitled, Miami, Florida, 1966, ©Gordon Parks Foundation

These photos, shot in 1966 and 1970, are now on view at Arnika Dawkins Gallery, an Atlanta, Georgia institution that specializes in the work of African American photographers capturing African Americans identities. Even today, Parks’ images stand out not only as uniquely revealing portraits of Ali, but as fragments of a different kind of photojournalism, one that, as Stephen Sommerstein recently put it, “understood composition as well as newsworthiness.”

See a preview of the photos on view here, plus a few examples of Parks’ previous work, many of which are also on view in Arnika Dawkins Gallery’s show, “Gordon Parks — American Champion.” For more on the wonder that is Gordon Parks, see our past coverage here and here.

Gordon Parks — American Champion will be on view at Arnika Dawkins Gallery until March 28, 2015. The Gordon Parks Foundation also recently released American Champion, a limited edition portfolio containing Parks’ photographs of Ali and a printed essay by David E. Little, Curator and Head of the Department of Photography and New Media at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.