Few books have become so universally beloved as Norton Juster and Jules Feiffer’s children’s novel The Phantom Tollbooth.

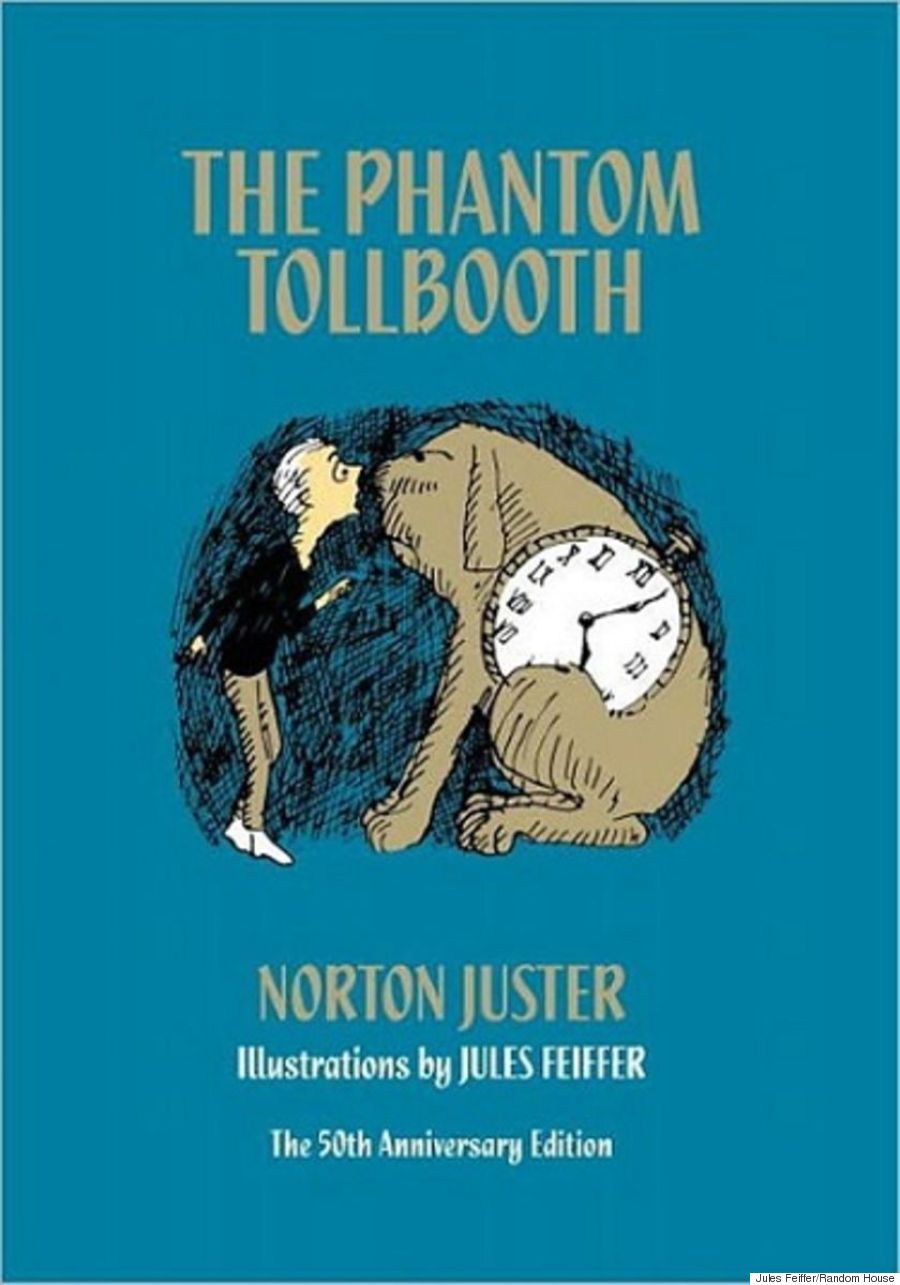

Though it’s not a picture book, the collaboration between writer Juster and illustrator Feiffer produced such a harmonious marriage between words and images that Feiffer’s sketches are thought of as inseparable from the text. In an age of collectible cover redesigns and repackagings, the original bright cerulean cover with Feiffer’s scratchy drawing of Milo and Tock reigns largely uncontested, familiar to generations of young readers.

Feiffer, however, harbored doubts about his work on the beloved children’s book. A new retrospective on his artwork, Out of Line: The Art of Jules Feiffer, by Martha Fay, sheds light on his ambivalence toward perhaps his most famous illustrations. Read an excerpt from Out of Line below:

Another collaboration he had mixed feelings about during this period was The Phantom Tollbooth, written by his good friend Norton Juster. When Juster began writing The Phantom Tollbooth in 1960, he asked Feiffer if he would illustrate it. Feiffer agreed, but as Juster recalled fifty years later, he was on-and-off a persnickety collaborator.

“There are a lot of things Jules doesn’t like to draw or can’t,” Juster says. “Either he thinks he can’t—or he just doesn’t want to do it. When we were working on The Phantom Tollbooth, one of the things I wanted to do was maps. Feiffer could not or would not draw a map. So I drew the map, and he put a piece of tracing paper over it and did it in his line.

“When it came to doing the armies of Wisdom, who are supposed to be mounted on horseback, the first time he showed me the sketch they were all mounted on cats because he doesn’t like to draw horses. We finally compromised, and he drew two lines that simulated the idea of a horse.”

In fact, says Feiffer, not long after the two friends completed their second project together, after a half-century gap, “I had very little regard for what I did on The Phantom Tollbooth. I thought the text was brilliant, and I thought I was imitating illustrators who were better than I was. I did the art on tracing paper.

“Those illustrations are now legendary, apparently. People say they treasure them— they’re their favorite part of the book—and I don’t respond to any of this. I look back on the work and I think it’s good work, but I can’t say I have any visceral response to it. Unlike The Odious Ogre [2010], the last book I did with Norton. There I take great pride in the work, and I think it’s one of the best things I’ve ever done, and I take it out and look at it with great admiration. But I don’t look back at The Phantom Tollbooth, except for a few drawings, as an example of my work that I like to be reminded of.”

Feiffer’s harsh judgment of his work on The Phantom Tollbooth aside, the bestselling book remains a beloved classic. “If stylistically the Phantom Tollbooth illustrations are not quite all of a piece,” writes Leonard S. Marcus, author of The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth (2011), “that is because Feiffer was borrowing left and right,” from “Winsor McCay, James Thurber, Edward Ardizzone, George Grosz, Thomas Rowlandson, and on and on. Even so, he more than acquitted himself, infusing the drawings with a kind of coiled-spring energy and blitheness of spirit that perfectly suit Juster’s outlandish tale.”

Note: As we were working on this monograph, a cache of drawings Feiffer did on tracing paper more than fifty years ago turned up unexpectedly in his studio.

Excerpt from Out of Line: The Art of Jules Feiffer

By Martha Fay ©2015 Martha Fay

Published by Abrams

Below are unpublished preliminary sketches, model sheets, and alternate character illustrations for the book:

– This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.