As yet another impressively long season of “The Good Wife” comes to a close on Sunday, The Huffington Post caught up with showrunners Robert and Michelle King. What will become of the show once Archie Panjabi (Kalinda) leaves? How do they change plot lines in real time? And how, in the name of merlot, do they keep up with TV’s “golden age,” in spite of the many restrictions that come with being on broadcast? Thankfully, you don’t have to wait until next season to find out.

Will’s death really revitalized the show. What will Kalinda’s departure mean for next season?

Robert King: I think it’s going to be a momentary depression because Kalinda has been such a driving interest for lot of fans. She’s a hard character to follow. It’s almost like you never want to follow Louis C.K. as a comedian. You don’t want to be the second one up. I think the problem is that Archie’s great performance and Kalinda’s strong character made such a gigantic impression on the show. But I do think there’s a sense that even when you lose a friend on “The Good Wife” you start to gain new ones and appreciate new ones.

Michelle King: Josh Charles’ [Will] departure was two thirds of the way through the season, so we had a lot of episodes to play after he left. I think it won’t be as hard because there are three or four months off between this season and next season.

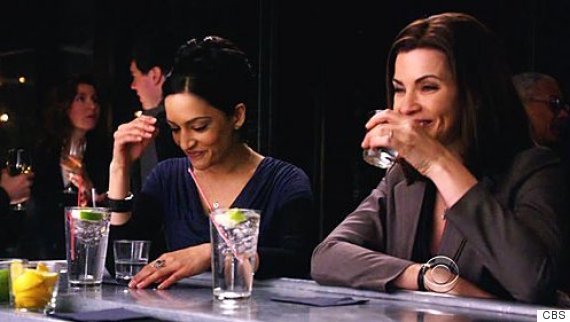

As of “The Deconstruction,” Archie (Kalinda) and Julianna (Alicia) went about 50 total episodes without filming a scene together. Can you speak to why they’ve been kept separate? They only spoke on the phone in the aftermath of Will’s death …

Robert King: They are going to be in a scene together.

Michelle King: It’s all character-based. And you will get to see them together again in the finale.

Robert King: I think the real key is Alicia’s scandal, and the aftermath has kind of left her a little adrift and created this new room for her to forgive and to apologize. So, I hope the viewers will like that final scene with them together, because both actresses did incredible work.

You’re able to react to audience reactions quite quickly. For example, taking out that plot line with Kalinda’s husband whom everyone hated. What kind of production schedule allows for that?

Robert King: In real time, there is probably two months between the writing of [an episode] and the actual showing of it on air. But that’s different at the beginning of the season. The beginning of the season we work over the summer to load up on five or six episodes that come before the actual premiere. So, that’s why with the Kalinda thing, you’re right, we did react to the viewers. But it wasn’t until the ninth episode that that reaction became evident, because we were so far ahead. Usually we’re only two months ahead. So, you can at least get a sense of where the viewers are. You want the viewers behind in your dramatic telling. You want this sense of, “Okay, we’ve gotta slow this down” or “We’ve gotta be paying more attention to how our storytelling is impacting viewers.”

Michelle King: And, of course, the editing is far closer to when the show airs. So, sometimes things get played with in the editing room to address issues.

Robert King: For example, here’s the thing, with [Episode 20, “The Deconstruction”] we wanted an additional scene. We wanted to see the recorded side of a phone call. So, we went on the “NCIS” set last week, I think it was that Thursday, shot it and then dropped in the episode that Sunday. I mean, that’s the closest we’ve ever been … basically four of five days before we show the episode.

What do you map out in the beginning of the season? There are definitely some long game narrative arcs. Peter’s workplace discrimination comes to mind.

Robert King: You’re right about that one. Another one last season was the NSA. What we map out is we know we want to plant a seed that will grow into a plant later in the year, but you may not know how big the plant grows, whether it’s going to be a tree or just a sapling. So, for example, with the African Americans and Peter firing them, we kind of accidentally stumbled into that in that we had some great actresses we wanted to use and we realized they were African American and all playing sort of villains to Peter.

Michelle King: What ended up happening is they were guest stars doing arcs on the show, but they weren’t series regulars. So we didn’t really have a tie to their time, but they kept — because they were so talented — getting cast as regulars in other shows. So, we kept losing these actors and we had to find a way to get them off the show so they would be fired or they would take another job within the “Good Wife” world. So, after that happened a couple of times we made something out of that.

Robert King: I would say, to answer your bigger question, we map out about 50 percent of what you see. I would say about half. The other half we want to leave open to what happens along the way.

There are so many restrictions you have to deal with by virtue of being on broadcast — product placement, advertiser demands, commercial breaks — how do these obstacles affect your creative process?

Robert King: Sometimes I think fewer options actually create great creative decisions. And the panic that we feel heading towards the deadline, sometimes makes it more intuitive how you’re writing and how the actors are acting and then the editors going with our gut on how we’re going to put it together. I think sometimes that is its own excitement. It’s the excitement of, “Let’s put on a play and we only have a week to do it — how are we gonna do it? Let’s go!” And I know there are so many good cable shows. That’s not to denigrate. Oh, my God, “The Americans” was so amazing this year. Not to denigrate what people are doing. But there is a kind of excitement to be working so fast. And it also gives you more options to do something crazy like, “Let’s do an episode that is all in Alicia’s mind.” You know, when you’re doing 22 [episodes], you’re not as worried about the preciousness of each episode.

What do you think of the (absurd) idea that “The Good Wife” is a show “for women”? How do you think turning female-led entertainment into a niche market affects TV?

Robert King: We’d rather not have it thought of as TV for women.

Michelle King: We don’t think of it that way at all.

Robert King: But can we say, if you think of comic women, how much better they have it in this decade than the ‘90s. You know, the comic women now from Kristen Wiig to Amy Schumer and Amy Poehler. And then we’re every week finding these great actresses that can play comic or broad. I think there’s one this coming week who’s very funny. Anyway, I just think it gives women more options. In movies, they’re seen as second or even third bananas. Or prostitutes or something that is a cliche of female parts.

Michelle King: Just looking at our regulars between Julianna and Christine Baranski, these are women that are not only spectacular dramatists but also so funny.

Oh, totally. Also, I think it was last week, there was a scene with Christine and two other women over the age of 40. That is so rare to see. I feel like you guys should win something.

Michelle King: With Linda Lavin too! She’s so spectacular. I lay awake and try to think of ways to bring her back into the show, because she’s so fun.

Robert King: But you’re right, there must be a Bechdel test that is about that, I don’t know what it is.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

– This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.